Pyramids and Squares

The Great Pyramid of Giza, also known as the Pyramid of Cheops, is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the Giza pyramid complex. It is located approximately 9 kilometres west of the Nile river at the old town of Giza, just about 13 kilometres southwest of the modern day Cairo. The pyramid is the oldest and most intact of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Egyptologists believe the Great Pyramid of Giza was built as a tomb for the pharaoh Khufu (Cheops) over a 20 year period and finished approximately in 2560 BC. Initially 146.5 metres (481 feet) tall, the pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years. The pyramid was built with such a high precision that the four sides of its base have an average error of only 58 millimetres in length.

Scholars estimate that the pyramid consists of around 2.3 million blocks, most likely from nearby quarries. The largest granite blocks weigh from 25 to 80 tonnes. Some of these blocks were transported to the building site from locations like Aswan, a city in the south of Egypt, more than 800 kilometres (500 miles) away. In total, around 5.5 million tonnes of limestone, 8,000 tonnes of granite, and 500,000 tonnes of mortar were used for the construction of the Great Pyramid.

Originally, the pyramid was covered by white casing stones made of highly polished limestone to form a smooth outer surface. Unfortunately, a severe earthquake hit the Giza pyramid complex in 1303 AD, loosening many of the outer casing stones. In the 14th and 19th century, most of the casing stones have been carted away from the great pyramids to build mosques and fortresses in and around Cairo. These limestone casings are still visible in parts of these structures. By contrast, the Great Pyramid’s surface seen today is actually its underlying core structure.

What’s the Side Length?

Suppose we are given the base area of the Great Pyramid of Giza. For the time being — to make things a bit easier — assume the pyramid’s base area to be a natural number: 52900 square metres. We are given the task to compute the side length of the pyramid’s base.

To make it more challenging, imagine we were beamed to Ancient Egypt. We have no access to a computer (not even a human one) and, thus, have to solve this problem by hand! Where do we start?

Well, based on what we learnt in the elementary school, the base area \(A_B\) of a right rectangular pyramid is the product of the base’ length \(l\) and its width \(w\). In other words, the base area of a right rectangular pyramid can be calculated as \(A_B=l\cdot w\).

Since the base area of the Great Pyramid of Gaza is (roughly) a square, the side lengths of its base are equal. So the Great Pyramid’s area is \(A_B=l\cdot l\) where \(l\) is the length of the base’ side. So finding the pyramid’s side length given its base area \(A_B\) is equivalent to computing the square root of \(A_B\).

While we learn the square roots of simple numbers like 9 or 16 in school, the question we need to answer here is how to compute the square root of an arbitrary natural number. Interestingly, it turns out that already the Babylonians — from around 1800 to 500 BC — knew how to approximate the solution to this problem. Luckily for us, we’re in ancient Egypt and so we can ask a very special guy to explain us how this actually works.

Say Hello to Heron of Alexandria (and the Babylonians)

Heron of Alexandria, one of the greatest experimenters of the antiquity, was a mathematician and engineer who lived around 60 BC in the city of Alexandria in Roman Egypt. Founded around a small ancient Egypt town ca. 330 BC by Alexander the Great, Alexandria is the second-largest city in Egypt and a major economic centre at the time of Heron.

During this time, Alexandria is the intellectual and cultural centre of the ancient world. With its Royal Library — the world’s largest library at that time — Alexandria attracts many of the greatest scholars, including Greeks, Jews and Syrians. The city is an important centre of the Hellenistic culture and remains the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt and the Roman province of Egypt for almost 1,000 years.

Heron is a lecturer in mathematics, mechanics, physics and pneumatics at the Musaeum, an institution similar to a modern-day university that, among other things, includes the famous Library of Alexandria. In addition to being a scholar, Heron is an inventor and an exceptional engineer. As an example, he invents a steam-powered device called aeolipile, a radial steam turbine which spins when the central water container is heated. Aeolipile is consider to be the first recorded steam engine.

Heron also constructs the history’s first vending machine. It takes a coin via a slot on the top of the machine and dispenses a set amount of holy water. When the coin is deposited, it falls upon a pan attached to a lever. The lever opens a valve and the water starts flowing out of the vending machine. The pan continues to tilt because of the weight of the coin until the coin falls off. When that happens, a counter-weight snaps the lever back and closes the valve. (In case you are puzzled about the detail level of this description: the vending machine is included in Heron’s list of inventions in his book Mechanics and Optics).

Other Heron’s inventions include a wind-wheel, the first construction to harness wind on land, mechanisms for the Greek theater including an entirely mechanical play powered by a system of ropes and knots, a force pump widely used in the Roman world, a syringe-like device to control the delivery of air and liquids, and a stand-alone fountain operating under self-contained hydrostatic energy.

Heron also describes a programmable 3-wheel cart powered by falling weights. The weights are attached to strings wrapped around the individual drive axles of the front wheels (each front wheel has its own axle and so the wheels move independently from each other). For every wind of the string, the falling weights make the front wheels turn and the cart goes forward. If you reverse the direction of the string, the cart will go backwards. Reversing the direction of the string for only one of the two axles makes the cart turn left or right. Moreover, using pegs inserted into the axles, you can first wind the string in one direction, then go around the peg and reverse the direction in which the string is wounded around the axle. This allows you to change the cart’s moving direction at “run-time”.

As a result, Heron’s programmable cart performs a series of pre-defined movements in arbitrary directions (backwards, forwards, left, and right), and the pattern in which the strings are wound around the axles constitutes what we can refer to as a (computer) program: a collection of instructions to perform a specific task when executed by a machine.

In Dioptra, his book on land surveying, Heron describes an odometer-like device for automatically measuring the distance traveled by a vehicle. The working principle of the device is based on the observation that a wheel of 4 feet diameter (as it was typically used in Roman chariots) turns exactly 400 times in one Roman mile. For each revolution, a pin in the axle engages a 400-teeth cogwheel which, in turn, makes a complete revolution per Roman mile. This, in turn, engages another gear with holes along the circumference where pebbles are located. The pebbles drop one by one into a box and the number of miles travelled by the vehicle can be determined simply by counting the pebbles. Thus, Heron’s odometer effectively counts in digital form. (And so Heron’s work on programmable and automated devices represents some of the first formal research in the field of computing.)

Luckily for us, Heron also knows a method for iteratively computing the square root of a natural number! He even described it in his work Metrica published around 60 AD so that later on, it became known as Heron’s method. Interestingly enough, while Heron was the first one to explicitly write down this method, there is indirect evidence that Babylonian mathematicians knew exactly the same method at least since 1600 BC (Heron is believed to have lived ca. 10 AD to 70 AD). The reason modern-day scholars believe this is the famous Babylonian clay tablet YBC 7289 which contains an accurate approximation of the square root of 2.

Anyway, let’s get down to the math now.

Meanwhile in Alexandria…

After a long walk through the ancient Alexandria, we finally meet Heron at the Musaeum, apparently on his way to give one of his lectures and obviously a bit late. In a hasty attempt to explain his method, Heron sketches some lines and numbers into the sand. The sketch looks similar to the picture below.

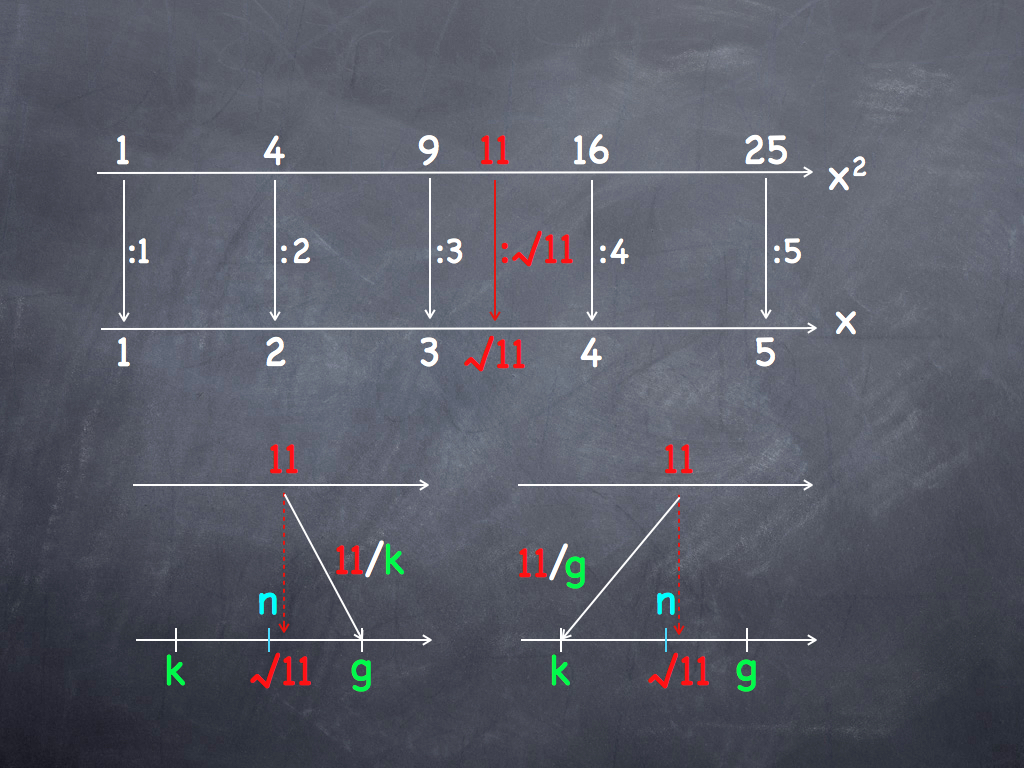

At the top of the picture, Heron draws two number lines. The lower number line, which he denotes by \(x\), shows the natural numbers from 1 to 5. The upper number line, denoted by \(x^2\), shows the squares of these numbers. Heron then draws vertical lines to indicate which squared numbers map to which natural numbers on the lower number line.

Clearly, determining the square roots of the numbers 1, 4, 9, 16, and 25 is easy because you know the multiplication table up to 9 \(\times\) 9. But how on earth, you ask, can we compute the square root of, say, 11?

Well, says Heron, using my method you can easily approximate the square root of 11 based on the following observation. If we take some natural number \(k\) that is smaller than the (unknown) \(\sqrt{11}\), then the resulting term \(11/k\) will be larger than \(\sqrt{11}\). To illustrate this, Heron quickly sketches a figure very much like the one seen at the bottom left of the picture above.

Similarly, he continues, if we divide 11 by a number \(g\) that is larger than \(\sqrt{11}\), the resulting term \(11/g\) will be smaller than \(\sqrt{11}\). He then sketches the figure seen at the bottom right of the above picture. In other words – Heron makes a short pause for more emphasis – if \(x\) is an overestimate of the square root of a non-negative number \(r\), then \(r/x\) will be an underestimate, and vice versa. Therefore, the average of these two numbers will provide a better approximation of \(\sqrt{r}\).

Now look again at the drawing, says Heron. If you compute \(n\), the average of \(k\) and \(g\), you will get a much better estimate for \(\sqrt{11}\). In the next step, you can use the new value \(n\) and compute the average of \(n\) and \(11/n\) to get an even more precise estimate. Thus, you can approximate the value of the square root of a non-negative number \(r\) by repeatedly applying this formula:

\[a_{n+1}=\frac{1}{2}(a_n + \frac{r}{a_n}).\]The symbol \(r\) denotes the radicand, in our case it’s 11. As a starting point, you should choose \(a_0\) to be somewhere near the actual square root of the radicand. As an example, we could choose \(a_0 = 3\) since 3 \(\times\) 3 = 9 is close to 11.

You can verify that Heron’s method works by trying it out for \(r=9\). For illustration purposes, assume we don’t know that the square root of 9 is 3 (but we guess it’s somewhere in the proximity of 3). So we can choose \(a_0 = 2\) and calculate \(a_1\):

\[a_{1}=\frac{1}{2}(2 + \frac{9}{2}) = 3.25\]Calculating \(a_2\) — the second iteration — gives us:

\[a_{2}=\frac{1}{2}(3.25 + \frac{9}{3.25}) = 3.009\]Finally, the third iteration yields the approximation \(a_3\):

\[a_{3}=\frac{1}{2}(3.009 + \frac{9}{3.009}) = 3.000\]Lo and behold — it works! Obviously, in the above calculations we rounded the result to three decimal places. Still, the method gives a precise estimation of the square root of 9 after just three iterations. So now, equipped with Heron’s method, we can tackle the task of computing the side length of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Look Ma, I Can Compute That Side Length!

Remember that — because we need a natural number to apply Heron’s method — we assumed the pyramid’s base area to be 52900 square metres. So let’s do the math. But instead of computing the \(a_n\)s by hand, let’s beam us back into the modern day and see what Heron’s method could look like when implemented as code. A very simple implementation in Python would be something like this:

def new(r, k):

return 0.5 * (k + float(r)/k)

def heron(r, k, n):

for i in range(0,n):

k = new(r, k)

print("=> %d: %.10f" % (i, k))

heron(52900, 2, 5)Executing the above Python script gives us:

$ python heron.py

=> 0: 314.5000000000

=> 1: 241.3517488076

=> 2: 230.2669593273

=> 3: 230.0001547493

=> 4: 230.0000000001We can easily check that 230 is the right answer by computing the square of it:

$ python

>>> 230 * 230

52900Et voilà!